What can the cost of homelessness tell us about solving it?

Author: Mike Allen, Advocacy Director, Focus Ireland.

Today we published the latest edition in our ‘Focus on Homelessness’ series looking at public expenditure on services for households experiencing homelessness (available here). The editorial approach of ‘Focus on Homelessness’ is simply to present the data, as published by the State, without commentary and even without analysis. The series comes from the shared belief of the School of Social Work and Social Policy in Trinity College and Focus Ireland that putting the data on homelessness into the public domain can help us arrive at a better understanding of this problem that causes such misery to so many, and also help us arrive at better solutions to it. Debate on homelessness has become so polarised that any analysis can be contested and might distract attention from consideration of what we know.

We are not naive and we know that publishing data in this way may result in only the most dramatic and superficial points being covered. If whatever coverage and debate arises from this publication concentrates solely on ‘homelessness cost over €2 billion since 2009’, we have not succeeded. That is why we organised a webinar to discuss the new report in detail (view the webinar here) and this accompanying blog to highlight Focus Ireland’s own analysis of what is important and telling in this data.

Emergency Shelter

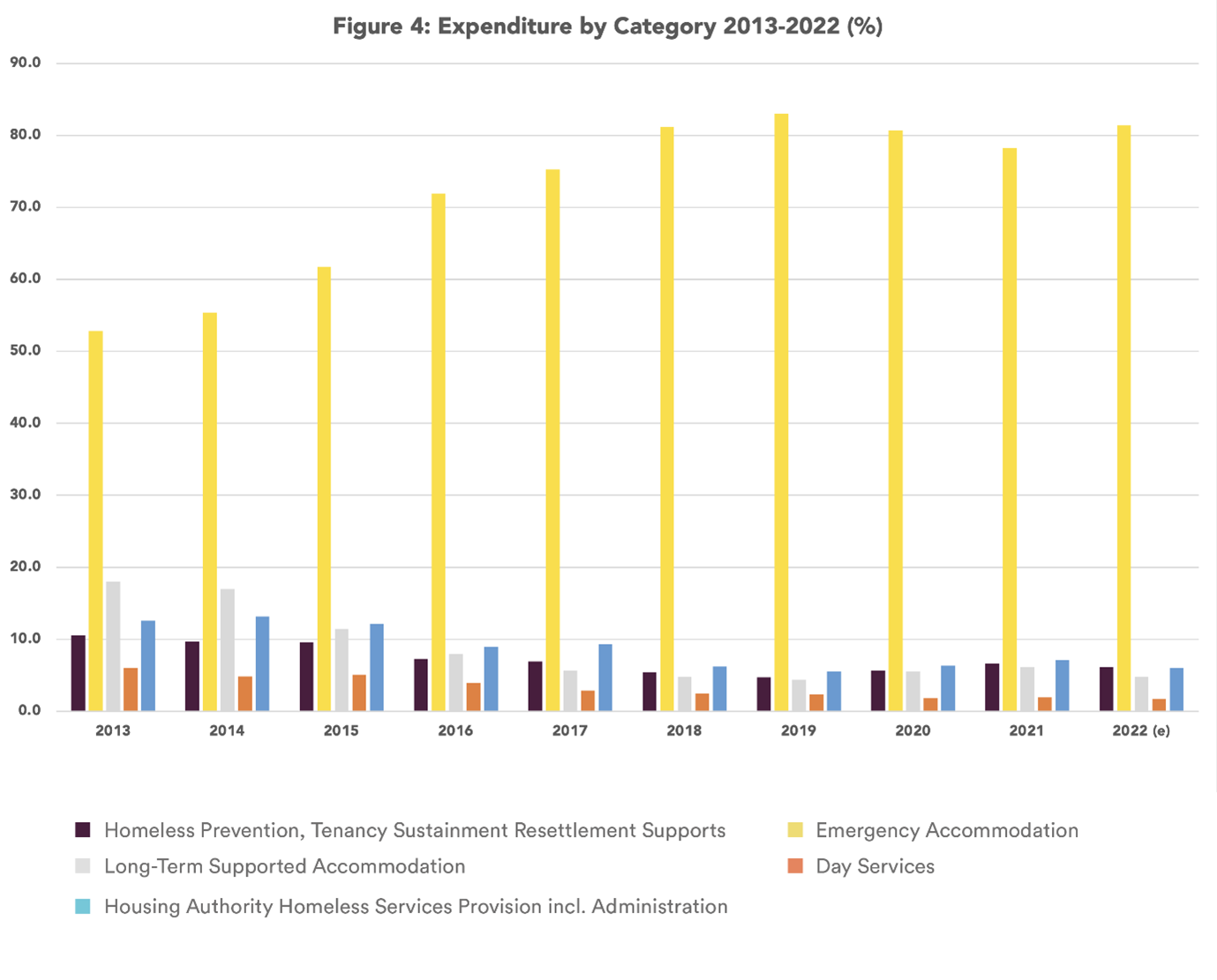

In our view, the most important issue here is not how much money is spent on homelessness but the fact that more than three quarters of it went on providing emergency shelter (Figure 4- see below). When we first did this analysis three years ago, we believed that the significance of this would be self-evident but as it turned out this was exactly what most people expected money to be spent on when tackling homelessness. This expectation reflects the predominant view of the nature of homelessness and contains within it the kernel of why we have made such little progress in tackling it.

Providing emergency shelter is enormously important. It provides a humanitarian response and ensures that people who are homeless are not forced to be ‘roofless’, to sleep rough, which the most extreme – and repugnant – form of homelessness.

The limitation with providing emergency shelter is that it does nothing to address the underlying issues. The problems that a person faces in the evening when they go into the homeless shelter remain unchanged when they wake to face another day.

I don’t just mean the fairly obvious point that providing emergency shelter does nothing to tackle the personal challenges that some people who are homeless experience – mental health or addiction. It also does nothing to change the underlying societal causes of the homelessness problem – such as high rents, housing insecurity or weaknesses in health supports.

Providing shelter does not change the underlying circumstances of the person or family in society. The shelter we gave yesterday has to be provided again today and again tomorrow.

On the other hand, some of the other categories of expenditure – prevention, tenancy sustainment, long-term accommodation can change the underlying circumstance and, in many cases, provide lasting solutions.

In other areas of social policy, and in particular labour market policy, the two types of intervention are called ‘active’ and ‘passive’ measures. Before the turn of the century, long-term unemployment was seen as the dominant social problem and there were enormous, co-ordinated efforts to tackle it across the EU and in Ireland. These policies were to a large extent successful and had at their core a determination to shift resources from passive measures and towards active measures – like, in this case, training, employment services etc. If we think of how we deploy our homeless resources in these terms, we can begin to understand why putting so much of our effort in passive supports has achieved so little.

Of course, the most important active support for people who are homeless is the provision of affordable housing, and that is why we have included Figure 8, as a first step in understanding this. However, while we believe provision of sufficient social housing is in itself a good thing, we can only really count social housing provision as an ‘active homeless measure’ to the extent that households that are homeless are at risk of homeless actually benefit form it. In Focus Ireland’s view, there is insufficient effort to mobilise social housing supply to tackle homelessness, this is a major theme of Focus Ireland’s work and we will return to that issue in future research.

This ‘active/passive’ analysis of funding, should also help us to think of homelessness as a dynamic problem. There is tendency to look at the increase in homelessness as a sort of building up. As if the over 8,000 adults who are homeless today comprise the 6,000 who were homeless two years ago plus all those who have become homeless since. In actual fact, over the period since 2014, a total of just under 49,000 adults have gone through homeless services for at least one night. In other words, the expenditure over this period needs to be seen as supporting over 40,000 adults out of homelessness as well as the 8,323 who are currently homeless.

Prevention

One of the relatively few good news stories in Irish homelessness is the extent to which successive Governments have adopted Housing First, set out a national strategy for its implementation and established a national office to support it. There are, of course, areas where we could do better – better integration of health supports, applying its lessons to families and young people, and of course access to suitable housing – but none of this should detract from the progress made with this effective approach.

Housing First expenditure is included in Category 1 (Homeless Prevention) (Fig. 4) and is one of the reasons for the welcome growth in this category from €5.7m in 2013 to €15.8m in 2022. The growth of Housing First is also one of the key drivers of the increase in Health expenditure on homelessness from €41m in 2020 to an estimated €50m in 2022 (Fig. 3).

However even this welcome increase in cash funding of prevention needs to be put in the context that the proportion of resources going to prevention fell from 10% in 2013 to only 6% last year.

Growth of private, for profit, providers

Not only are we spending most of our resources on emergency shelter, we are spending an increased proportion of that on private, for profit providers (Fig 5). The European Observatory on Homelessness Report puts this Irish experience in a wider European context. At the start of the current crisis in 2013, four out of every ten euro spent on emergency shelters went to private, for profit, providers. By 2021 this had risen to almost 6 euro in every ten (56%) – and we were spending much more. Over the 9 years from 2013-21 almost €600 million (€595.3m) of the funding for emergency homeless shelters went to for-profit providers – far exceeding the €380.7m going to the charitable NGOs – the ones which everyone has heard of. The report states that the proportion going to the for-profit providers is estimated to have increased still further in 2022 so that nearly 2/3 of expenditure on emergency shelter will be going to private providers.

The quality of physical accommodation and household services which these private operates provide varies, and we recognise the work being done to establish better physical standards for private providers. But there is one thing that these private providers have in common – they are not concerned with helping to end the homelessness of the people they accommodate. Sometimes, homeless NGOs are funded by local authorities to provide support to households in such private emergency accommodation (for instance the Focus Ireland Family Homeless Action Team is funded by Dublin Region Homeless Executive to provide such support in Hubs operated by private entities) but such expenditure is accounted for under Category 1, so it is safe to say that this massive increase in Category 2 expenditure is almost entirely passive – that is, it responds to the problem of ‘rooflessness’ but makes no contribution to solving the problem of ‘homelessness’.

In the highly charged political atmosphere in which homelessness is currently discussed, it is important to state that this has not been driven by any overt ideological agenda. There is no stated public policy intention to ‘privatise’ homeless provision, and nor am I aware of any unstated such policy either.

How we got here

I want to highlight two of the reasons that we have got into this situation.

The first is a widespread misunderstanding of homelessness as equating to rough sleeping. Despite the fact that rough sleeping accounts for only around 1 in every 100 persons who is homeless, media coverage of any form of homelessness is routinely accompanied by a picture of a person in a sleeping bag. The same assumption is quietly at play when Government Ministers explain why an eviction ban was needed before and but should not continue. Ministers repeatedly refer to the problems of ‘winter’ and ‘meteorological’ issues[1], reflecting an assumption that homelessness means being on the streets and exposed to the elements.

Irish people care deeply about homelessness, but when that caring equates homelessness with rough sleeping the resulting political pressure means we end up with more and more homeless shelters instead of more homes.

The European report points us in the direction of the second factor – the tendency to treat each new increase in homelessness as a ‘temporary problem’ requiring a short-term or ‘overflow’ solutions. If you believe – or for political reasons have to present – a problem as transitory, then more temporary shelters seem like an adequate response and the private sector provides a good solution. NGOs always want longer term commitments, look for skilled staff and push for standards.

The homeless system we have built is the result of year after year of short-term ‘fixes’ which turned out to be needed in the long term. We could say that, if we had understood that homelessness would grow to this extent we would have built a very different sort of homeless service. I would prefer to hope that if we had acknowledged the scale of our housing/homelessness problem we would have taken a whole range of different policy options which would have avoided so much trauma to so many.

The cost of ending the eviction ban…

Discussing hurried, short-term responses to long-term issues perhaps brings us finally to how this publication relates to the current dispute about the ban on no fault evictions from private rental accommodation.

To a large extent, the debate about the eviction ban has been frames as a question of how to balance ‘the interests of landlords’ with ‘the interests of tenants’. The Taoiseach has argued that the Government decision is ‘in the public interest’ and in this he seemed to be referring to hope that discontinuing the ban would help to convince landlords not to sell up.

While the interests of the landlords and tenants are part of the ‘public interest’, there are broader issues and one of these is the public cost of the policies under discussion.

There is very limited information about how much homelessness costs, in financial terms. In this publication we have presented a fairly generalised approach – simply taking the average number of households that are homeless during a year and dividing it into the cost of providing emergency accommodation. This approach, of course, blends in the very different costs of providing accommodation to single people and to families, and also blends in the cost of providing ‘shelter and dinner only’ accommodation with purpose-built units with qualified case managers. Noting these significant limitations, we estimate the cost of providing emergency accommodation to each homeless household for 2022 as having been €34,000, with the cost in Dublin rising to €39,000.

For every 100 households that enter homeless services as a result of being evicted, we can expect to see over €3m added to the cost of homelessness. While by no means all tenants who receive a NoT end up homeless (and not all homeless households got there via a NoT), landlords reported issuing over 5,500 NoTs in the 6 months prior to the eviction ban being introduced. Whatever the ultimate cash cost of this, it will overwhelmingly be paid to private property owners to provide emergency accommodation. This is not to in any way ‘demonise’ such property owners. It is by no means certain that we can find enough of them to provide the emergency accommodation we will need.

The data

Finally, it is worth noting that the data which we have drawn is essentially a neglected legacy of decisions made back in 2013. The then Government set up a ‘National Data Sub-Group’ comprising officials from national and local government, researchers from NGOS and academics. It was chaired by Prof Eoin O’Sullivan. This group proposed the regular publication of homeless data (although the group proposed it be published quarterly, and the Department decided to publish monthly) and a framework for collecting regional data on a quarterly basis.

In a properly functioning policy development system, the data reported in these quarterly reports would have been scrutinised by a collaborative team of officials, academics and service providers. This would have led to refinements not just in expenditure policy but also in data collection. Instead, the Data Sub-Group was discontinued around 2015 and in all probability, Prof O’Sullivan was the only person who read them for several years.

While there have been welcome efforts under the current Minister to publish some of the data in quarterly reports, there has been no return to a collaborative, independent expert-led approach to collecting and analysing the data. Thus, the data here merely reflects back to us how we have floundered in the waves of the crisis, rather than providing us with a firm footing on which to base our response.

As in all the ‘Focus on Homelessness’ publications our aim is to provide evidence for a constructive debate, but this also implies a call for structures in which that debate takes place. The current Minister’s National Homeless Action Committee provides an ideal opportunity to re-establish something like the Data Sub-Group so that this material is more effectively used to improve policy, planning and practice.

Without that change of approach, we will be trapped in the spiral of spending increasing resources on interventions that make no lasting difference beyond the night on which they are spent.

The new edition of Focus on Homelessness Report on Public Expenditure is available here.

[1] For instance: Dail Question from Deputy Ivana Bacik to Minister Darragh O’Brien PQ [11835/23] 8th March 2023