Shining a spotlight on women’s homelessness this #IWD2023

Author: Emma Byrne, Policy Officer, Focus Ireland.

On International Women’s Day 2023, Focus Ireland reflects on the current state of women’s homelessness in Ireland and highlights the importance of developing services and policy responses that respond better to the unique needs and experiences of women. This is even more urgent than ever as figures show a 49% rise in the number of women homeless in the last two years.

The latest official homeless figures show there are currently a record 11,754 people homeless and relying on emergency homeless accommodation (EA) as of January 2023. Of the 8,323 adults in emergency homeless accommodation over 3,000 are women, or 36% of all adults homeless. Furthermore, there are 1,609 families homeless, and 55% of these families are headed by a lone parent of which the vast majority are women[1].

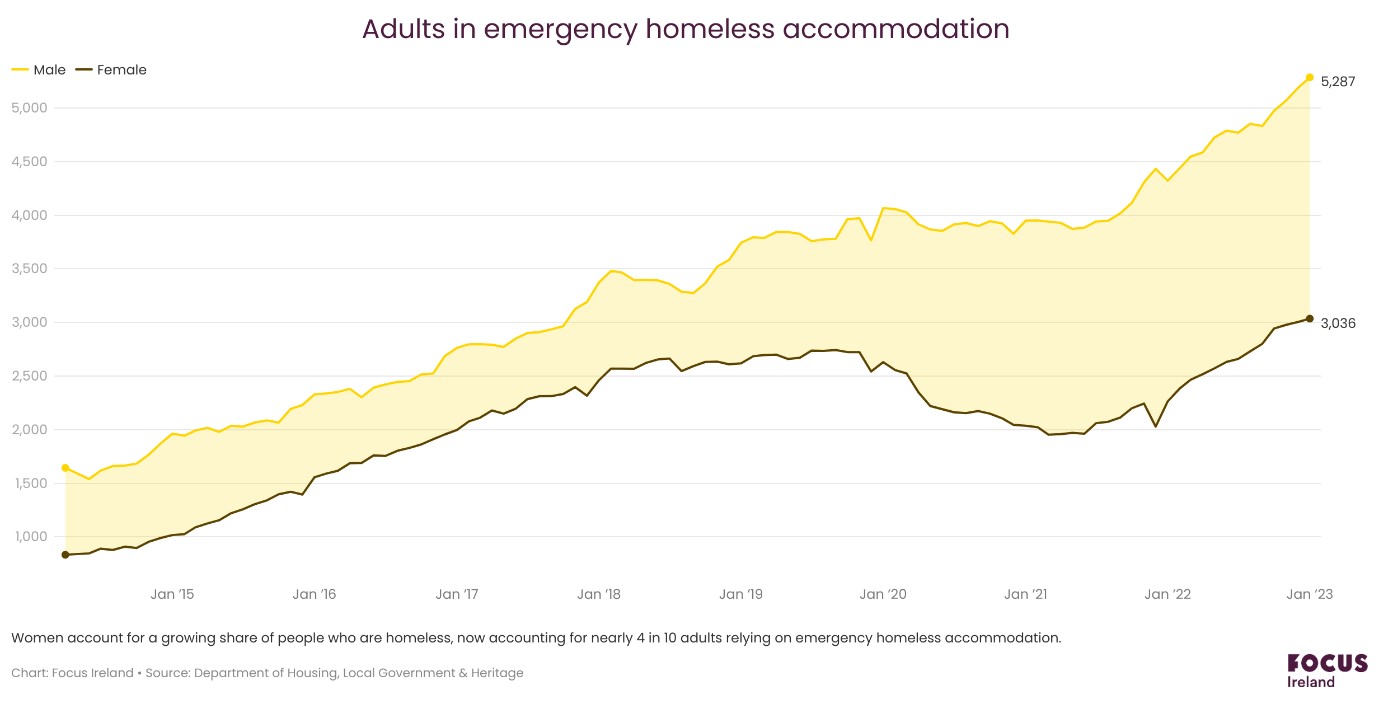

When you look behind the numbers (See Figure 1) it shows that there has been considerable fluctuation in the total number of women in emergency homeless accommodation over the last two years. Between 2014 to early 2020, the trajectory of male and female homeless was quite similar, rising every year and at a comparable rate with some slight increases and decreases during this period.

However, in early 2020, the growth rate of men and women in homelessness began to diverge as the number of women in emergency accommodation began to fall considerably while the number of men in EA plateaued. In March 2021, the lowest number of women in emergency accommodation was recorded since December 2016 when there were 1,953 women in EA. However, since early 2022 the number of women in homelessness has been steadily increasing, and the number of women in emergency accommodation reached a record high of 3,036 in January 2023. This means there’s been a shocking 49% rise in the number of women homeless in the last two years. The total has shot up from 2,037 in Jan 2021 to 3,036 women homeless in Jan this year. This record figure does not even include women in domestic violence refuges or others “sofa-surfing” with friends or family to keep a roof over their heads.

Figure 1:

The decline and rise of women’s homelessness in the last two years in many ways mirrors the same fluctuations as the number of families in homelessness (see here). The emergency rental protections that were in place on and off from March 2020 to April 2021 in response to the Covid-19 public health emergency coincided with a decline of 43% in family homelessness and 23% in women’s homelessness during this period. The number of men in emergency accommodation only declined by 3% during the same period.

As well as increased rental protections in the first year of the Covid-19 public health emergency that likely prevented new entrants to homelessness, huge efforts were made to support people, and particularly families, out of homeless emergency accommodation with an urgency rarely seen before. Moreover, the rapid constriction of the tourist market at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic increased the number of available properties to rent for long-term use in the early months of the pandemic with Daft.ie reporting that the number of properties for long-term rent in Dublin city centre increased by 64%, and 13% nationally, in March 2020.[2]

This increase in the number of long-term rental properties supported families in particular to exit homelessness in the private rental market using the Housing Assistance Payment. Family homelessness has subsequently increased from early 2022 onwards, with the number of families homeless increasing 44% between January 2022 and January 2023.

While similar patterns are evident between the number of women in homelessness and the number of families homeless since early 2020 it is important that women’s homelessness is not simply viewed as synonymous with family homelessness, as this does not capture the unique trajectories and experiences of all women who accessed emergency accommodation during that period.

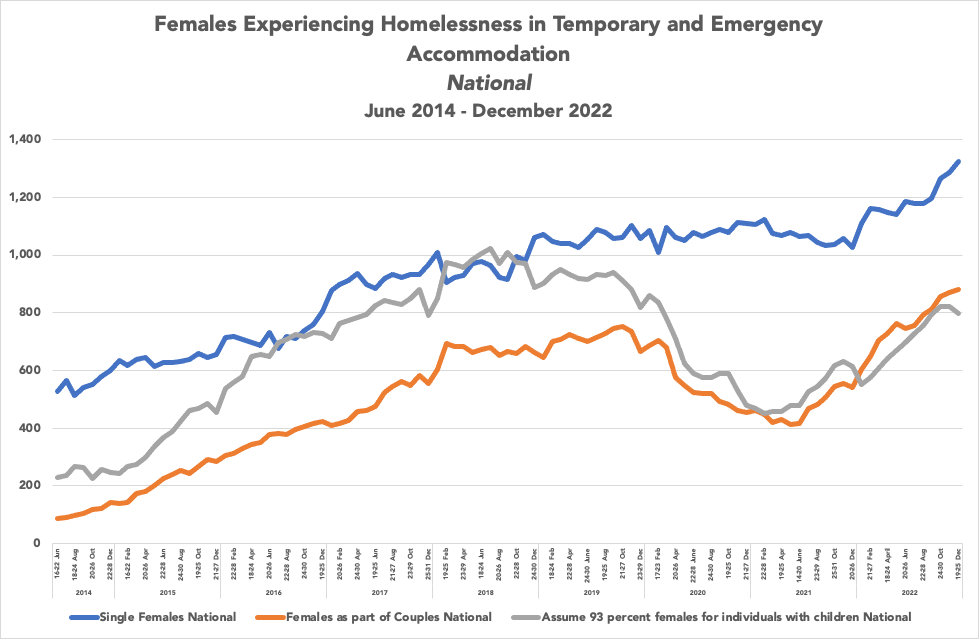

As shown in Figure 2 (and previously outlined in this Focus Ireland report), while the number of women in families, both as part of a couple [3] and lone parents (presumed to be 93% women), did decline in a similar trend to the number of families in homelessness, the number of ‘Single’ women, i.e., women without accompanying children, plateaued throughout much of 2020 and 2021 rather than decline and began to rise from early 2022 again. This is similar to the plateau and the increasing trend observed in the number of men in emergency homeless accommodation during the same period as shown in Figure 1.

Homelessness has traditionally been seen as an issue that only affects single men and in the last decade or so, the growth of family and child homelessness has rightfully received significant attention. However, it is important that women experiencing homelessness without accompanying children are not forgotten. Figure 2 clearly shows the importance of not equating women’s homelessness with family homelessness, as this approach fails to capture the full picture of female homelessness. Women who are experiencing homelessness often face additional challenges when they present as homeless outside the domestic sphere and false assumptions and stereotypes can be made about these women (Bretherton & Mayock, 2021).

Figure 2:

Evidence shows that the pathways into homelessness, and the needs of women in homelessness, differ to men (Bretherton & Mayock, 2021). Although by no means the sole cause of women’s homelessness, gender-based violence is a worryingly common pathway for women into homelessness and organisations supporting women experiencing domestic violence expressed concern over the increase in incidents during the Covid-19 restrictions. Reports from organisations working on the frontline reported a 43% increase in contact in 2020 compared to 2019, and the Gardaí reported a 17% increase in calls related to domestic abuse in 2020 compared to 2019. The lack of affordable housing to support people trying to escape domestic violence contributed to an alarming finding from Mayock and Nearly (2022) published by Focus Ireland, which found that in some cases the lack of suitable accommodation drove some people back to the abusive situation from which they had fled, as they felt they had no other secure housing option (Read more here on why housing should be at the heart of responding to domestic violence).

Research also suggests that women are more likely than men to delay presenting to homeless services, resulting in more complex support needs, and an increased likelihood of trauma (Bretherton & Mayock, 2021). This delay in presentation suggests that many women experience ‘hidden homelessness’ and may not be captured in Irish homeless data which only records people staying in emergency homeless accommodation and excludes women and children staying in domestic violence refugees.

This is why it is critical that policy responses and services supporting women experiencing homelessness are designed and implemented with a gendered lens in addition to being trauma-informed, to ensure that the unique needs and trauma experienced by women is recognised and integrated into the support they receive. Policy responses to homelessness in Ireland have been largely ‘’gender-blind’’ and rarely mention the unique challenges faced by women who have experienced homelessness.

For example, the Housing First National Implementation Plan 2022-2026, the main policy response to support individuals without accompanying children who have experienced chronic homelessness, makes no mention of the gendered dimension of homelessness and how this can impact the supports that may be needed to support a woman as part of the Housing First programme.

This International Women’s Day 2023 is a stark reminder of the State’s largely gender-blind policy approach to women’s homelessness and provides an opportunity to focus on the unique challenges that women face in their pathways into homelessness, their experiences of being in homelessness, as well as the additional barriers that can impact their exit from homelessness.

We must improve our understanding of women’s homelessness and in particular the intersection of race, sexuality, age, gender identity, and ethnicity, and how this can interact with women’s homelessness and critically we must develop services and policy responses that respond better to the unique needs and experiences of women.

Further reading on women’s homelessness:

- Bretherton and Mayock (2021) WOMEN’S HOMELESSNESS: European Evidence Review

- Mayock, P. and Sheridan, S. (2012) Women’s ‘Journeys’ to Homelessness: Key Findings from a Biographical Study of Homeless Women in Ireland.

- NCWI (2018) The impact of homelessness on women’s health

- Mayock and Neary (2022) Domestic Violence & Family Homelessness

- FEANSTA (2022) HOUSING FIRST & WOMEN: Case studies from across Europe

- O’Sullivan et al (2021) Focus on Homelessness: Gender and Homelessness

[1] The breakdown of adult homeless data compiled and published by the Department of Housing records adults in emergency accommodation as either ‘male’ or ‘female’, no other gender preferences or pronouns are given as an option.

[2] https://www.irishexaminer.com/news/arid-30989241.html

[3] The current data only allows us to assume that all couples are heterosexual and does not allow for us to distinguish if any parents are in non-heterosexual couples.

Focus Blog

What does the expenditure on homelessness tell us about the our approach to tackling homelessness?

Despite its technical title, the Focus on Homelessness report “Public Expenditure on Services for Households Experiencing Homelessness” (March 2025), paints a vivid picture of how we have responded to the enduring homelessness crisis over the last decade. The picture it paints is not one driven by vision or ideology, but rather a reactive response which constantly underestimates the scale of the challenge and consumes resources trying to contain, rather than solve, the problem. It also provides hints about what we could do better.

Minister should rethink proposal to remove ‘no fault eviction’ safety net

Minister for Housing, James Browne, has proposed changes to the‘Tenant in situ’ scheme which, while he presents them as ‘refocusing on families’ and ‘new funding’, in reality, will take away the safety net from people facing homelessness due to ‘no-fault evictions. Focus Ireland has written to the Minister, asking him to reconsider the proposal.

What is Youth Homelessness?

Youth homelessness means people aged 13 -26 who are without stable accommodation and staying in hostels, temporary accommodation, couch surfing or rough sleeping. They are facing homelessness at a crucial point in their emotional, cognitive and social development while transitioning from adolescence to adulthood

Where do potential Coalition partners stand on homelessness?

Housing and homelessness was the most important issue for most people in last Friday’s general election, according to Irish Times/RTÉ/TG4/TCD exit poll, with 29% of voters saying that it was their top issue when voting. With all seats now filled, and several potential coalition outcomes now possible, negotiations around housing will likely be one of the deciding factors on whether parties choose to form a coalition government together over the next few weeks.

Non stop increase in adult-only homelessness over last decade shows we need a serious rethink

Our new report shows that adult-only homelessness has been allowed to steadily increase, year on year since 2014, we now have triple the number of homeless adult-only households than we did just a decade ago.

Youth Homelessness: An Obvious Opportunity for Homelessness Prevention

To mark UN International Youth Day, this blog post takes a look at this youth homelessness from the perspective of homelessness prevention. If we wish to truly end homelessness, as we have committed to working towards by 2030, then we must prevent youth homelessness.

Shining a spotlight on women’s homelessness this #IWD2023

On International Women’s Day 2023, Focus Ireland reflects on the current state of women’s homelessness in Ireland and highlights the importance of developing services and policy responses that respond better to the unique needs and experiences of women. This is even more urgent than ever as figures show a 49% rise in the number of women homeless in the last two years.

The winter eviction ban and homelessness: early evidence

The Government’s hasty introduction of a Winter Eviction Ban has failed to halt the rise in the total number of individuals in homelessness so far. The November 2022 homeless figures are the first to reflect the impact of the ban, which came into force at the start of the month but, rather than the decrease that some had predicted, they showed a further increase of 145 to yet another new record level.

An international perspective on Irish homelessness policy

‘From Rebuilding Ireland to Housing for All: international and Irish lessons for tackling homelessness’ was launched in September this year, receiving widespread positive coverage. Here we asked the lead researcher, Professor Nicholas Pleace of York University, to write a guest blog, setting out the main conclusions from the project.

Causes of Family Homelessness in the Dublin Region during the Covid-19 Pandemic

While Covid-19 supended life as know it in 2020, this global disaster has been slowly but surely subsiding. With the roll-out of new vaccines, economies, and societies, have reopened. However, one of the more problematic issues pre-Covid, the use of emergency accommodation to house people experiencing homelessness, is again being used at a much higher rate in the last year.

Why are the numbers of people homeless at record level and what can be done to stop further increases?

With homelessness reaching a new record level in July, this blog looks at why homelessness has risen by 30% in the last year and what immediate and long-term actions must be taken now if we are to stop homeless from rising further.

Solidarity with Young People, Challenging Youth Homelessness: Focus Ireland Youth Services and Advocacy

In recognition of UN International Youth Day, this blog will highlight the risks faced by certain young people in terms of homelessness and housing insecurity, and the supports and services Focus Ireland is providing to address them.

Understanding housing inequalities: The disproportionate risk of homelessness facing migrants living in Ireland

March 2022 saw a sharp rise in the proportion of people with European Union or European Economic Area (EU/EEA) citizenship newly presenting to homeless services, according to figures reported by the Dublin Regional Homeless Executive (DRHE). The increase sparked media speculation concerning the causes of this, the role played by migration, and the implications of this apparent trend for homeless services and the housing sector in general. However, the most recent DRHE Monthly Report to Dublin City Councillors on Homelessness shows that the proportion of new presentations from persons with EU/EEA citizenship markedly fell to a more typical level in April.

Welcome decrease in rough sleeping as adult-only homelessness at record level in Dublin

There was a welcomed slight decrease in the number of individuals found rough sleeping in Dublin in Spring 2022 according to figures published by the Dublin Region Homeless Executive (DRHE) last week . The Official Spring Count of people sleeping rough in the Dublin Region was carried out over the week March 28th – April 3rd and identified a total of 91 individuals confirmed as rough sleeping during the week.

Review of 7 years of spending on homelessness shows it’s time to change

In the first Special Edition of our Focus on Homelessness series, we are looking at Expenditure on Services for Households Experiencing Homelessness. In this blog post, Director of Advocacy Mike Allen outlines why we need a deeper understanding of this, and how this Edition does this.

Why we need an inclusive High Road Covid-Era Back to Work Strategy

In the space of just a few weeks, Covid-19 has fundamentally reconfigured the relationship between welfare and work in Ireland. In this blog post, Dr Mary Murphy, Senior Lecturer at Maynooth University, examines why we need an inclusive high road back to work strategy as we transition out of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Covid-19 and building a society where we can all have a home to stay put in

The Covid-19 pandemic puts people who are homeless at risk disproportionate risk – not only are they more likely to have underlying health issues, they are unable to follow the key recommendations –wash your hands regularly, stay at home and keep a ‘social distance’ from other people.

Understanding the December 2019 homeless figures – Part 1

Having access to accurate numbers is key to informing policy and services responses designed to tackle homelessness. It is equally vital to have the information behind the numbers to be able to clearly understand trends as they develop.